>

It’s that time of year again. Spring has sprung, flowers are in bloom, and lovers of all ages are busily preparing to tie the knot. The months of May and June are traditionally amongst the most popular for nuptials, and so I figured this is a good time to survey the most famous (and infamous…) weddings in cult-television history.

Before we get to my top ten selections, I should note that there are other contenders for “greatest cult-tv wedding” beyond those featured in the countdown. These episodes, while entertaining, are bridesmaids but never brides, you might conclude.

Lois and Clark: The New Adventures of Superman (1992-1996), for instance, saw Clark Kent’s (Dean Cain) wedding day spoiled when bride Lois Lane (Teri Hatcher) was replaced at the altar by a frog-eating clone. The real wedding took place a season later and was not only uneventful, but sort of an anti-climax.

On Star Trek: Voyager’s (1995 – 2001) “Course: Oblivion,” Tom Paris (Robert Duncan McNeill) and B’Elanna Torres (Roxann Dawson)were married in the Delta Quadrant, but the ceremony viewers witnessed turned out to be that of a duplicate or “alternate” crew that was fated to die. Because of this plot twist, the wedding felt like just another gimmick in an already gimmicky narrative.

Weddings have been a staple of other genre programs too. Buffy the Vampire Slayer’s “The Prom” teased an Angel/Buffy wedding day that quickly became a nightmare, and The Greatest American Hero’s (1981-1983) “Newlywed Game” saw Ralph (William Katt) and Pam (Connie Sellecca) tie the knot under some less-than-ideal circumstances.

As much as I enjoy all of these series, I suppose you could say I have “cold feet” about including them in this particular wedding party. So without further ado, here are — from ten to one — my selections for the best cult-tv wedding days in history.

The Ten Greatest Weddings in Cult-TV History

10. Star Trek: “Balance of Terror” (1966)

Two young crew-members aboard the U.S.S. Enterprise, Angela Martine and Robert Tomlinson, celebrate their joyous wedding day aboard ship. Scotty (James Doohan) gives away the blushing bride, and Captain Kirk (William Shatner) officiates at the ceremony, Yeoman Rand (Grace Lee Whitney) at his side.

Kirk’s opening words: “Since the days of the first wooden vessels, all ship masters have had one happy privilege: that of uniting two people in the bonds of matrimony.”

Unfortunately, Kirk’s happy duty is interrupted by a crisis in the Neutral Zone that separates the United Federation of Planets from the Romulan Star Empire. A “ghost” ship is destroying Federation outposts one by one, leaving carnage in its wake. The ship is really a Romulan Bird of Prey, armed with a devastating cloaking device and a new plasma weapon. What ensues is a battle between two equally-matched opponents and commanders. Kirk is victorious in the space battle but, as always, there is a price for such conflict. The young groom, Tomlinson, is killed in the final battle, leaving a heartbroken fiancee, Angela, behind.

“Balance of Terror” reminds us that even in victory, there is often loss; that every time war is the solution to a political problem, the cost comes in human lives. The ship’s teaser involving the wedding is a perfect reminder of this fact. In this case, a couple’s dream of future happiness is the victim of the Romulan/Federation conflict.

And for noble Captain Kirk, he must reckon with the fact that though he handily completed his mission (destroying the Romulan vessel and her weapons), it was by no means a painless or easy campaign. As he knows too well, a Captain is responsible for his crew, and here he loses two young people who should have been destined for happiness. Weddings are universally about the future, about bringing together promising tomorrows. In “Balance of Terror,” the wedding only precedes a terrible ripping asunder.

09. Buck Rogers: “Escape from Wedded Bliss” (1980)

The Draconian Princess, Ardala (Pamela Hensley) returns to Earth with an orbital doomsday weapon and demands that Buck Rogers (Gil Gerard) marry her, lest she destroy the world. The Earth Defense Directorate surrenders Buck to the Princess aboard her flagship, the Draconia.

There, Buck learns the rules of Draconian courtship and marriage. In short, he must battle Tigerman in the arena to prove he is worthy of a Draconian princess. Then, in the final stages of the wedding ceremony, Buck is to wear not a traditional wedding ring, but rather a wedding collar which constricts and tightens around his neck when he displeases his new bride. This “shotgun wedding” is averted at the last instant, and Buck destroys the doomsday weapon, leaving a jilted Ardala at the altar.

“Escape from Wedded Bliss” is a primal male fantasy. A gorgeous, powerful and sexy princess will destroy the world unless

you and only you agree to make her your bride? What red-blooded American guy wouldn’t be in favor of that arrangement? Then again, there’s the wedding collar to think about…

But all kidding aside, this episode of Buck Rogers in the 25th Century does a pretty fine job of revealing how sad and lonely a figure Princess Ardala truly is. As a member of Draco’s royal family, Ardala feels isolated and alone, and suspects that Buck — because of his “out-of-time” nature — might feel those emotions too.

Joining up makes sense, at least from Ardala’s perspective. Forcing Buck Rogers to marry her isn’t the answer, but this is one Bridezilla who you can really feel compassion and even admiration for. Ardala knows what she believes will make her happy, and goes for it, doomsday weapon, wedding collar, combat-to-the-death and all. In short, “Escape from Wedded Bliss” humanizes one of the series’ recurring villains in a very sympathetic way. It also reminds the viewer that marriage is best left for people who are truly and irrevocably in love. And as Buck reminds Ardala (with surprising tenderness) in “Escape from Wedded Bliss,” he just doesn’t love her.

08. Star Trek: Deep Space Nine: “You Are Cordially Invited” (1997)

Pour the blood wine. Serve the steaming hot g’agh. It’s Dax’s Big Fat Klingon Wedding.

On Deep Space Nine — in the midst of the galactic war with the Dominion — Worf (Michael Dorn) and Lt. Jadzia Dax (Terry Farrell) plan to wed in a traditional Klingon ceremony.

There’s only one hitch in this plan: the mistress of the House of Martok, Sirella, isn’t exactly keen on having a non-Klingon such as Dax as a family member. Dax refuses to humble herself for the proud Sirella, and it looks like the wedding won’t come off unless she changes her mind.

Klingon bachelor parties aside, this episode of

Deep Space Nine gazes at the underlying meaning of marriage:

the total combination of two lives and the total dedication of one life to another. Dax shouldn’t exactly be surprised that her hubby-to-be, Worf, so deeply desires a traditional Klingon wedding, and she shouldn’t be surprised that she must jump through some hoops to win over her future “in-laws,” given Klingon pride and xenophobia.

With a little help from Captain Sisko, Dax realizes that she must give her soul-mate the wedding he wants, and that it is actually only her own pride standing in the way. There are plenty of times in marriage when the only way to get over a problem is to tuck away the ego and make a sacrifice for the spouse, and this episode understands that fact. If Dax is going to be part of the family, she has to respect family tradition, and again, that’s something that all prospective brides and grooms realize. It would have been interesting, however, to see Worf doing some compromising too, however. Would he have done anything for Dax to experience a traditional Trill wedding, I wonder?

07. Battlestar Galactica: “Lost Planet of the Gods” (1979)

While the rag-tag, fugitive fleet faces two problems, a deadly plague

and a strange “void” in space, Captain Apollo (Richard Hatch) and former news-woman, Serina (Jane Seymour) select a date for their “joining” ceremony, to be officiated by Commander Adama (Lorne Greene).

Apollo and Serina’s “sealing” ceremony is celebrated in a candle-lit chamber beneath the darkness of the starless void, but at the height of the nuptials, a star appears to guide the Galactica and her wards to a planet called Kobol, the very world from which all Colonial life sprang.

Apollo and Serina explore the planet with Adama and encounter Baltar — and tragedy — on the planet surface.

“Lost Planet of the Gods,” like so much of

Battlestar Galactica’s canon, concerns a Manichean universe of light and dark; a theme made all the more explicit by the episode’s plot element of the starless void. But even in a universe of moral absolutes (rather than the moral relativity of the recent re-imagination…), the Gods may yet be fickle. The “joining” of Apollo and Serina seems pre-ordained and sanctified by the sudden, almost divine appearance of Kobol’s star. But what the Gods give, they can also take away.

In the last act, when Serina dies from Cylon attack, there’s not any talk of signs or portents. There are no bright stars guiding anyone to happiness. Instead, it’s a very human tragedy, and the last scene in the episode — Apollo and Serina’s son, Boxey (Noah Hathaway) saying goodbye to the beautiful wife and mother — never ceases to affect on a human level.

A lot of people claim Battlestar Galactica was just a Star Wars rip-off and the characters were only carbon copies of Star Wars characters. A lot of people were wrong.

“Lost Planet of the God’s” tragic ending proves that rather conclusively. I often liken Battlestar Galactica to Little House on the Prairie or The Waltons in Space: every week a family tragedy, and a family overcoming that tragedy together. The last shot of “Lost Planet of the Gods” is heart-wrenching, but also a testament to the strength of family bonds: Adama, Tigh, Starbuck and Apollo’s other friends all stand outside Serina’s door, waiting for him, and silently supporting him and Boxy through their difficult loss.

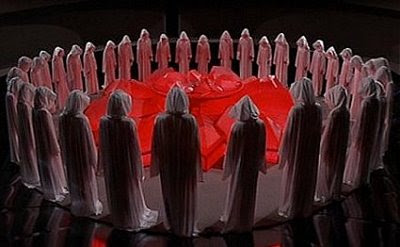

06. V: The Series: “The Rescue” (1985):

The bride wears scales. The priest is a lizard in cardinal hat. And the wedding banquet consists of gerbils, spiders and rats. The bride, Diana (Jane Badler) and groom, Charles (Duncan Regher) share not a delicious wedding cake, but rather “a ceremonial mouse” at the lovely reception.

Yep, it’s just another day aboard the Visitor mothership in

V: The Series.

Here, Diana is manipulated into marriage by her rivals Lydia (June Chadwick) and Charles. Surprisingly, however, Diana and Charles actually seem to fall in love, or at least in lust. This development outrages Lydia, who then plots to kill Diana with “cat poison.” The murder attempt goes wrong, however, and it is Charles who ends up dead on his wedding night.

From start to finish, “The Rescue” is utterly outrageous. It’s high camp and V: The Series knew it. Why? Well, consider that on July 29, 1981, a very different Charles and Diana were wed at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London before a global TV audience of one billion people. “The Rescue’s” Charles/Diana nuptials were not viewed by nearly so many, but it was worth a try, wasn’t it?

The fun of this episode (and of

V: The Series in general) was in watching the wicked, wicked machinations and tactics of Lydia and Diana as they forever sought to one-up each other, all while devouring small rodents and other terrestrial creatures.

“Peel you another goldfish?”

05. Dexter: “Do You Take Dexter Morgan?” (2008)

In the finale of season three, sociopath, serial killer and blood spatter expert Dexter Morgan (Michael C. Hall) finally marries Rita (Julie Benz), but only after tying up some serious loose ends regarding his “Dark Passenger.”

These loose ends involve the final disposition of Miguel (Jimmy Smits) and Ramon Prado (Jason Olazabal), two men who had learned his secret.

Dexter Morgan remains one of the truly great characters in modern television history, and “Do You Take Dexter Morgan” asks many important questions about Dexter’s nature.

Is he capable of love? Is he capable of participating in an honest and open relationship with anyone given his murderous nightlife?

Surprisingly, the answers to both those questions seem to be yes, at least with a few caveats. In the course of the story, Dexter learns that Rita is keeping secrets too. She has been married twice before, not once before, as he believed. But Dexter decides not to confront Rita about her lie when he realizes the truth of the marriage’s circumstances.

Already then, Dexter has taken a critical step towards compassion and mercy. One thing about marriage: you have to permit your spouse a few secrets and a few fantasies. After all, Dexter’s hiding a few things too, right? Marriage is not just about romance, but about acceptance and forgiveness. If a sociopath can learn that simple lesson, we all can.

04.

Smallville: “Promise” (2007)

In the spring of its sixth season, Smallville reached a pinnacle of darkness. Lana Lang (Kristin Kreuk) had accepted Lex Luthor’s (Michael Rosenbaum’s) marriage proposal and rejected Clark Kent (Tom Welling) over his penchant for secrecy.

“Promise” takes viewers through the Lex/Lana wedding day with a surfeit of surprises and heartbreaking twists.

Lana finally learns Clark’s secret and has serious second thoughts about marrying Lex. Meanwhile, Lex’s secret about Lana’s pregnancy threatens to come to light, and leads him to commit bloody murder…in the chapel. Clark makes a last minute play for Lana and considers proposing to her. Finally, Lionel Luthor (John Glover) steps in and blackmails Lana into marrying his son. Trapped in a loveless relationship, Lana leaves Clark abandoned and rejected on a particularly sad wedding day.

In the first seven seasons, Smallville was both the epic heroic journey of Clark Kent and the tragic fall of Lex Luthor. Thus Clark and Lex were deliberate mirror images; a reminder in some fashion that parenting can make all the difference in the path a child takes towards adulthood. Showered with love and nourished on bedrock Kansas family values, Clark grew up feeling loved…and so could become a hero. Lex, on the other hand, had every monetary advantage anyone could possible get, but his father never loved him, and this absence of love sent him down the dark path.

In “Promise,” the wrong man clearly wins Lana’s hand. Through manipulation, exploitation and ultimately murder, Lex takes away from Clark the woman he loves. On the other hand, it’s not a great victory for Lex, either. Lex must resort to brutal murder with his bare hands to keep his wife-to-be, bloodying his white tuxedo shirt on his wedding day. Their marriage is also predicated on a lie of his making, regarding her unusual pregnancy.

And then the kicker: even after murder, the love of Lana is not assured for the young billionaire. In the end, Lana only remains with Lex because of Lionel’s blackmail. Lex Luthor may be on the ascent in “Promise,” but he is an authentically tragic figure, doomed to always be alone because of his suspicion and controlling personality.

But “The Promise” thrives because it demonstrates how lack of trust can scuttle a marriage from the get-go, from the words “I do.” Lana and Lex’s wedding night is certainly bound to be uncomfortable, given that Lex is a murderer and Lanais staying in the relationship only to protect Clark’s life…

03. Buffy the Vampire Slayer: “Hell’s Bells” (2002)

In the sixth season of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Xander (Nicholas Brendon) is finally about to marry former wish-demon Anya (Emma Caulfield) when he encounters a mysterious future version of himself.

This old, hunched, “Future Xander,” shows his younger self disturbing visions of an unhappy married life, and Xander gets really cold feet.

In truth, Future Xander is a demon seeking revenge against Anya, but his real identity is beside the point. Rattled, Xander leaves a heart-broken Anya at the altar, leading her to resume her career as a demonic destroyer of men.

Buffy the Vampire Slayer’s season six was all about real life as the “Big Bad.” Buffy had to take a job at a fast food restaurant to support her family, Giles left for England, Willow developed an addiction (to magic), and Xander and Anya went through the “Hell’s Bells” marriage disaster.

The point is that making big life choices — even without the involvement of the demonic or supernatural — always has unintended repercussions. And weddings, of course, have repercussions too. Xander has the proverbial “cold feet” in “Hell’s Bells,” but he lets his fear sway him, and breaks the heart of a woman who loves him dearly.

This one act of betrayal leads Anya back into the demon fold, and promises more trouble for Xander and the scoobies. But again, this is real life. You don’t leave a person at the altar without creating some serious bad blood. How often have we seen that amongst former spouses, now estranged or divorced? Someone you loved so passionately becomes someone you hate more than anyone else in the world. Love and hate, not so far apart?

02. Star Trek: “Amok Time” (1967)

“The Trouble with Tribbles” may be funnier. “City on the Edge of Forever” may be more tragic.

But Theodore Sturgeon’s “Amok Time” is nonetheless one of Star Trek’s finest and most memorable hours.

In “Amok Time,” Spock experiences Pon Farr, the Vulcan urge to mate. This biological drive is so strong that Spock (Leonard Nimoy) will die if it is not fulfilled. Acting as a friend and disobeying orders, Captain Kirk takes the Enterprise to Vulcan. so Spock can marry…and mate.

Spock asks Kirk and McCoy (De Forest Kelly) to attend the wedding ceremony on Vulcan’s surface, officiated by the great T’Pau (Celia Lovsky). There, the Enterprise triumvirate also meet Spock’s intended, the lovely T’Pring (Arlene Martel). Unfortunately, T’Pring has no desire to marry Spock, and in an ancient ritual, forces Spock to fight for her hand in marriage. Her chosen champion? Captain Kirk…

It’s funny that the logical Mr. Spock should be carried off to the altar, essentially, in a swirl of irrational, uncontrollable emotions. But that happens to men and women on Earth too. And if so many of the episodes on this list indeed detail the passionate emotions that swirl around weddings and marriage, “Amok Time” is a nice reminder that not all marriages emerge from feelings of love. T’Pring has no desire for Spock, no desire to be the wife “of a legend,” and would rather see him die in a ritual than spend her life with him. She is a cool, cruel, callous “thinker” who believes she has found a “no lose” scenario for herself. And in the end, she’s absolutely right; she is victorious.

The callous T’Pring is strongly contrasted in “Amok Time” with the dedicated friendship of Kirk/Spock/McCoy. While T’Pring thinks only of herself, the Enterprise trio are a textbook case of one for all/all for one. This is a reminder, perhaps, that there are other kinds of real love besides romantic/sexual love.

and finally…

01.

Smallville: “Bride” (2009)

It’s the day of Chloe Sullivan’s (Allison Mack) long-awaited wedding to cub reporter Jimmy Olsen (Aaron Ashmore). The location of the nuptials: the Kent farm in Smallville, Kansas.

While an anxious Lois Lane (Erica Durance) organizes the event, Chloe receives distressing voice mails from Davis Bloome (Sam Witer), who has only recently acknowledged his love for Sullivan.

At the wedding reception — and caught on digital video — an inhuman beast called Doomsday lays siege to the barn and abducts Chloe, leaving Jimmy bleeding to death.

Bride” arrived at a time of tremendous dramatic resurgence for Smallville. The episode moves at light-speed, yet still finds the time to develop the burgeoning Lois-Clark (Clois?) relationship. It balances this new love with a story of love rejected, in the case the love for Chloe of the “monster,” Doomsday. Additionally, “Bride” often adopts the first person perspective of wedding video footage (think Cloverfield [2008]) as the monster arrives to take his bride.

Given the narrative details (and title), this episode of Smallville is also rife with allusions to monster movies such as Bride of Frankenstein (1935). The visual of the monstrous Doomsday carrying Chloe in her wedding gown to the Brainiac-infected Fortress of Solitude is one straight out the genre’s golden age, and enormously resonant in this context. Doomsday sets Chloe down on a bed of black ice, and her eyes glitter…not with love; but with the inhuman glare of Brainiac.

Besides the powerful imagery, technique and characterizations, “The Bride” somehow still finds time to re-introduce Lana Lang to Smallville (thus setting back Clark and Lois six months or so…) and then ends with the revelation that Lex Luthor is alive, and bent on vengeance. Clark and Lana? Clark and Lois? Jimmy’s Dead? Doomsday? Brainiac? Lex Luthor? “Bride” is a prime reason why Smallville’s fans are still so die hard. When the show hits on all thrusters, it’s like a Kryptonite kick to Superman’s gut.

“Bride” is truly apocalyptic, a wedding day gone straight to Hell. And the episode is so dramatic, so fast-paced you won’t be able to catch your breath until the end credits roll. If marriage is about being swept away by love, “Bride” sweeps you away in love gone horribly wrong.

So that’s the top ten cult-tv wedding list. Speak about it now, or forever hold your peace…