As I’ve mentioned before, I often receive e-mails asking me to review specific films. One of the most oft-requested reviews is for Star Trek V: The Final Frontier (1989), which is widely-regarded as the worst Star Trek film to feature the original cast.

I don’t know this for certain, but I strongly suspect this particular review is requested in the hope that somehow, in some way, this poorly-reviewed William Shatner film might be rehabilitated in popular imagination. For instance, requests for a review of Star Trek V: The Final Frontier spiked after my positive review of The Motion Picture. My supposition thus leads me to believe that a lot of Star Trek fans must — secretly? — enjoy the oft-derided fifth film, and are seeking valid, well-enunciated arguments in support of it.

I can relate to that. Big time.

After all, I am a Star Trek fan, and can see the silver-lining in every Star Trek movie. So I am happy to enumerate the aspects I appreciate and admire about Star Trek V: The Final Frontier.

However, for the record, it is also necessary for me to note where and when things go dramatically wrong with the movie. So — to quote Joss Whedon — this review isn’t going to be all “hugs and puppies.”

That fact established there are indeed many components of Star Trek V: The Final Frontier worth lauding and I will explain in detail below why I feel that way.

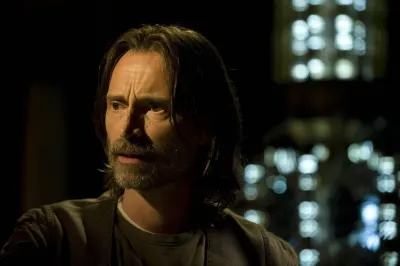

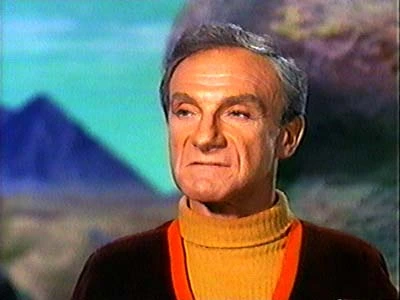

Let’s start, however, with a brief re-cap of the plot. The fifth Star Trek picks up with Captain Kirk (William Shatner) and his crew on vacation on Earth — in the paradise-like setting of Yosemite — when a dangerous hostage situation unfolds in the Neutral Zone. There, on Nimbus III — on the “planet of Galactic Peace” — a Vulcan renegade named Sybok (Laurence Luckinbill) has taken hostage the Romulan, Klingon and Federation counsels. He has done so with an army of devout “believers.” Sybok’s gambit is to capture a starship so he can set a course for the center of the Galaxy and find the mythical planet Sha Ka Ree (named after Sean Connery), where he believes “God” awaits.

An unprepared U.S.S. Enterprise, with only a skeleton crew aboard, is assigned to rescue the hostages. The attempt fails, and Sybok commandeers the Enterprise using his particular brand of Vulcan brainwashing to persuade the crew to follow him. In particular, he frees each man he encounters of his “secret pain.” Kirk soon learns that Sybok is Spock’s (Leonard Nimoy) half-brother, a heretic who rejected Vulcan dogma and came to believe that emotion, not logic, is the key to enlightenment.

With a Klingon bird of prey in hot pursuit, the Enterprise passes through the Great Barrier at the center of the galaxy and encounters a mysterious planet. There, on the surface, awaits a creature who claims to be “God.” Kirk questions the Being, and soon a vision of Heaven goes to Hell.

Because It’s There: The Search for the Ultimate Knowledge; The Search for a Film’s Noble Intentions

From Captain Kirk’s effort to climb El Capitan at Yosemite National Park in the film’s first scene to Sybok’s probe through the foreboding and mysterious Great Barrier, Star Trek V: The Final Frontier concerns, in large part, a typically-Star Trek conceit: the human quest to reach a higher summit and to find at that apex a new or deeper truth about our existence.

When Mr. Spock asks Kirk why he would involve himself in an endeavor as dangerous as climbing a mountain, Kirk answers simply, “because it’s there.” That’s a simplistic but apt shorthand to describe one of our basic human drives. What our eyes detect, we want to explore, to experience. Enlightenment, for us, is often attained on the next plateau.

Sybok terms his search for “God” the search for the “ultimate knowledge” and he too seeks to climb a mountain after a fashion: penetrating the Great Barrier which protects a secret at the center of our galaxy. The means by which Sybok conducts his quest are not entirely kosher, however (kidnapping diplomats and hijacking a starship). But his quest, though coupled with his vanity, is sincere. An outcast among his Vulcan brethren, Sybok believes that if he can “locate” God, his beliefs will be validated, and thus perhaps re-examined by those who made him a pariah.

At one point late in the film, Kirk seems to suddenly realize that Sybok and he share a similar drive; that he has stubbornly refused Sybok the same liberty he affords himself, not merely to “go climb a rock,” but to see, literally, what awaits at the mountain-top. Upon this realization, Kirk gazes knowingly at an old-fashioned captains’ wheel in the Enterprise’s observation deck. His hand brushes across a bronze plaque engraved with the legend “Where No Man Has Gone Before,” a re-iteration of the franchise’s “bold,” trademark phrase. In a world where so many sci-fi movies depend on black-and-white portrayals of “good” and “evil,” it’s quite bold that The Final Frontier actually establishes a connection — and one involving the meaning of life itself — between protagonist and antagonist.

It should be noted here, perhaps, that Star Trek V: The Final Frontier is not out on some wacky limb, franchise-wise, in exploring the existence of “God,” or a planet from which life sprang. On the former front, the Enterprise encountered the Greek God Apollo in the second-season episode “Who Mourns for Adonis” and on the latter front, discovered the planet “Eden” in the third season adventure “The Way to Eden.” In a very real way, The Final Frontier feels like a development of this oft-seen Trek theme, as much as The Motion Picture was a development of themes featured in episodes such as “The Changeling” and “The Doomsday Machine.”

What remains laudable about Star Trek V: The Final Frontier, however, is that screenwriter David Loughery, with director Shatner and producer Harve Bennett, carry their central metaphor — discovery of the ultimate knowledge — to the hearts of the beloved franchise characters. Star Trek V very much concerns not just the external quest for the divine, but a personal and human desire to understand the meaning of life.

Or, at the very least, the path to understanding the meaning of life.

What that desire comes down to here is one lengthy scene set in the Enterprise observation deck. There are no phasers, transporters, starships, Klingons, or special effects to be found. Instead, the scene involves Kirk, Spock, Bones and Sybok grappling with their personal beliefs, with their sense of personal identity and history, even. Sybok attempts to convert Spock and McCoy to his agenda by using his hypnotic powers of the mind. “Each man hides a secret pain. Share yours with me and gain strength from the sharing,” he offers. One at a time, Kirk’s allies crumble under the mesmeric influence. Then Sybok comes to Kirk, and the good captain steadfastly refuses Sybok’s brand of personal enlightenment.

In refusing to share his pain, Kirk notes to Dr. McCoy (DeForest Kelley) that “you know that pain and guilt can’t be taken away with a wave of a magic wand. They’re the things we carry with us, the things that make us who we are. If we lose them, we lose ourselves. I don’t want my pain taken away! I need my pain!”

This specific back-and-forth is the heart of Star Trek V: The Final Frontier. The Kirk/Sybok confrontation embodies the difference between Catholic Guilt (as represented by Kirk), and New Age “release” (as represented by Sybok). In terms of a short explanation, Catholic guilt is essentially a melancholy or world-weariness brought about by an examined life. It’s the constant questioning and re-parsing of decisions and history (some call it Scrupulosity). And if you know Star Trek, you understand that this sense of melancholy is, for lack of a better word, very Kirk-ian.

As a starship captain, James Kirk has sent men and women to their deaths and made tough calls that changed the direction of the galaxy, literally. But he has never been one to do so blindly, or without consideration of the consequences. “My God, Bones, what have I done?” He asks after destroying the Enterprise in The Search for Spock, and that’s just one, quick example of his reflective nature. In short, Kirk belabors his decisions, so much so that McCoy once had to tell him (in “Balance of Terror”) not to obsess; not to “destroy the one called Kirk.”

What Captain Kirk believes – and what is crucial to his success as a starship captain — is that he must carry and remember the guilt associated with his tough decisions. He must re-hash those choices and constantly relive them, or else, during the next crisis, he will fail. His decisions are part of him; he is the cumulative result of those choices, and to lose them would be — in his very words here — “to lose himself.” Pain, anguish, regret…these are all crucial elements of Kirk’s being, and of the human equation.

By contrast, Sybok promises an escape from melancholy. His abilities permit him to “erase” the presence of pain all-together. This a kind of touchy-feely, New Age balm in which a person lets go of pain (via, for example, ACT: Active Release Technique) and then, once freed, suddenly sees the light.

Sybok’s approach arises from the counter-culture movement of the 1960s (the era of the Original Series), and might be described — albeit in glib fashion — as “Do what feels right” (a turn-of-phrase Spock himself uses in the 2009 Star Trek). But Sybok is a master of semantics. He doesn’t “control minds,” he says, he “frees” them. Left unexamined by Sybok is Kirk’s interrogative: once freed from pain, what does a person have left? What remains when a person’s core is removed? An empty vessel?

Isn’t pain, borne by experience a part of our core psychological make-up? The New Age depiction of Sybok in Star Trek V: The Final Frontier led critic David Denby to term this entry “the most Californian” of the Star Trek films (New York, June 19,1989, page 68).

In countenancing the false god of Sha Ka Ree, these belief systems collide. Sybok — freed of pain and self-reflection — is unaware of his own tragic flaws. Eventually he sees them, terming them “arrogance” and “vanity.” But Kirk, who has always carried his choices with him, is able to face the malevolent alien with a sense of composure and entirely appropriate suspicion. Kirk is able, essentially, to ask “the Almighty for his I.D.” because he has maintained his Catholic sense of guilt. He’s been around the block too many times to be cowed by an alien who wants to appropriate his ship.

The lengthy scene in the observation deck, during which Sybok attempts to shatter the powerful triumvirate of Kirk, Spock and McCoy is probably the best in the film. Shatner shoots it well too, with Sybok intersecting the perimeters of this famous character “triangle” (of id, ego, and super-ego) and then, visually, scattering its points to the corners of the room when doubt is sewn.

And then, after Kirk’s powerful argument and re-assertion of Catholic Guilt, the triangle (depicted visually, with the three characters as “points”) is re-constructed. Sybok is both literally and symbolically forced out of their unified “space.”

In point of fact, Shatner uses this triangular, three-person blocking pattern a lot in the film. Variety did not like the movie, but noted the power of this particular sequence in its original review: “Shatner, rises to the occasion,” the magazine wrote, “in directing a dramatic sequence of the mystical Luckinbill teaching Nimoy and DeForest Kelley to re-experience their long-buried traumas. The re-creations of Spock’s rejection by his father after his birth and Kelley’s euthanasia of his own father are moving highlights.”

While discussing Shatner, I should also add — no doubt controversially — that Shatner boasts a fine eye for visual composition. The opening scene on the cracked, arid plain of Nimbus III, and the follow-up scene set at Yosemite reveal that he has an eye not just for capturing natural beauty, but for utilizing the full breadth of the frame. As a director, Shatner came out of television (helming episodes of T.J. Hooker), but his visual approach doesn’t suggest a TV mentality. On the contrary, I would argue that there are moments in Star Trek V: The Final Frontier that are the most inherently cinematic of the film series, after Wise’s Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979) and Abrams’ big-budget reboot of 2009.

What Does God Need With a Starship? Pinpointing the Divine inside The Human Heart and in the Natural World

I’ve noted above how Star Trek V: The Final Frontier involves the search for the ultimate knowledge, and uses two distinctive viewpoints (Catholic Guilt embodied by Kirk and New Age philosophy embodied by Sybok) to get at that knowledge.

What’s important, after that “quest” is the film’s conclusion about the specific “ultimate knowledge” gleaned from the journey.

In short order, in Star Trek V: The Final Frontier, the angry Old Testament-styled God-Alien reveals his true colors and demonstrates a capricious, violent-side. After Kirk asks “what does God need with a starship,” “God” is wrathful and violent. And this is what the site Common Sense Atheism suggested was really being asked by our secular, humanist hero.

“One might ask, “What does God need with animal sacrifice? With a human sacrifice? With a catastrophic flood? With billions of galaxies and trillions of stars and millions of unstoppably destructive black holes? What does God need with congenital diseases and a planet made of shifting plates that cause earthquakes and tsunamis? Isn’t the whole point of omnipotence that God could make a good world without all these needlessly silly or harmful phenomena?”

Moreover, why should humans obey the commands of someone as capricious, jealous, petty, and violent as the God of the Jewish scriptures?

This critical line of thought reminds me of my experience seeing Star Trek V: The Final Frontier in the theater with my girlfriend at the time, a devout Jew.

Afterwards, she was utterly convinced that Kirk and company had indeed encountered the Biblical, Old Testament God. And that they had, in fact, destroyed Him. Her reasoning for this belief was that “God” as depicted in the film actually looked and acted in the very fashion of the Old-Testament God.

On the former, front (God’s appearance), The Journal of Religion and Film, in a piece “Any Gods Out There?” by John S. Schultes, opined: “This being appears in the stereotypical Westernized figure of the “Father God” as depicted in art. He has a giant head, disembodied, depicting an older man with a kind face, flowing white hair and booming voice.”

On the latter front — behavior — there are also important commonalities. The Old Testament God was cruel, self-righteous, unjust, demanding, and acting according to a closely-held personal agenda (moving in a mysterious way?) without thought of courtesy or explanation to humans. Consider that the Old Testament God destroyed whole cities (like those of Sodom and Gomorrah), and that it’s his plan to kill us by the billion-fold in the End Times, if we don’t believe in him. The Old Testament God is indeed one of violence and punishment.

And this is precisely how Star Trek V: The Final Frontier depicts this creature. He wants to deliver his power — his violence and judgment — to “every corner of creation.” Naturally, Kirk can’t allow this brand of subjugation…even it comes from God.

Over the years, I have come to agree more and more with my former-girlfriend’s assessment. The alien portrayed in Star Trek V: The Final Frontier may indeed be the Old Testament God of our legends. Just as Apollo was indeed, Apollo of Greek Myth in “Who Mourns for Adonis.”

And, in fact, Captain Kirk kills God here. (Or rather, it’s a cooperative venture with the Klingons…). In doing so, Kirk frees humanity (and the universe itself) from the oppression of superstition, judgment and tyranny. Ask yourself, keeping in mind Gene Roddenberry’s visions of humanity and religion (expressed candidly in the TNG episode “Who Watches the Watchers”): is that Star Trek V’s ultimate message?

The ultimate knowledge, according to this Trek movie is that God only exists “right here; the human heart,” as Kirk notes near the film’s conclusion. Accordingly, The Journal of Religion and Society explains that this conclusion represents a narrative wrinkle true to “the collective history of Classic Star Trek,” a re-assertion of Roddenberry-esque, secular principles. In his essay, “From Captain Stormfield to Captain Kirk, Two 20th Century Representations of Heaven, scholar Michel Clasquin concludes:

“In “Final Frontier“, Heaven turns out to be Hell: the optimism is deferred until the heroes have returned to the man-made heaven of the United Federation of Planets. The film ends where it began: with Spock, Kirk and McCoy on furlough in a thoroughly tamed Earth wilderness. This, the film tells us, is the true Heaven, the secular New Jerusalem that humans, Vulcans and a smattering of other species will build for themselves in the 24th century, a world in which the outward heavenly conditions reflect the true Heaven that resides in the human heart.”

Clasquin’s point here absolutely demands a re-evaluation of the book-end Yosemite camping scenes of Star Trek V: The Final Frontier. Many critics complained that the film takes a long time to get started, since the crew must “laboriously” be re-gathered from vacation.

However, if Star Trek V: The Final Frontier’s point is that “God” resides in man’s heart (and is, in fact, man himself) and that the Garden of Eden, or Heaven itself is “a tamed Earth wilderness,” — a finely-developed sense of responsible environmentalism, in fact — then these two sequences of “nature” prove absolutely necessary in terms of the narrative. Heaven on Earth is within our grasp, the movie seems to note. We don’t have to die to get there. We merely must act responsibly as stewards of our planet (or in Star Trek’s universe, planets, plural). The human heart, and the Beautiful Earth: these are Star Trek V: The Final Frontier’s (atheist) optimistic views of where, ultimately, Divinity resides. If you desire a Star Trek movie with some pretty deep philosophical underpinnings, look no further than William Shatner’s The Final Frontier.

“All I Can Say is, They Don’t Make ‘Em Like They Used To: A Movie Shattered (not Shatnered…) by Poor Execution”

William Shatner handles many of the visual aspects of Star Trek V: The Final Frontier with flair and distinction. His impressive efforts are badly undercut, however, by three catastrophic weaknesses. The first such weakness involves studio interference in the very story he wanted to tell. The second involves inferior special effects, and the third involves slipshod editing.

On the first front, William Shatner sought initially to make a serious, even bloody movie concerning fanatical religious cults and God imagery. His plan was shit-canned in large part, by Paramount Studios. Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home (1986) had just proven a major success, and the Powers That Be judged this was so because the movie evidenced a terrific sense of humor, particularly fish-out-of-water humor. The edict came down that Star Trek V: The Final Frontier had to include the same level of humor.

Frankly, this edict was the kiss of death. The humor in Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home grew organically out of the situation: advanced people of the 23rd century being forced to deal with people and activities of the “primitive” year 1986. The scenario there called for fish-out-of-water humor, and no characters were sacrificed on the altar of laughs.

Above, I described the thematic principles of Star Trek V: seeking the ultimate summit both externally and internally, and discovering that the Divine is inside us — or is, actually, the Human Heart. So how exactly, does Scotty knocking himself out on a ceiling beam, or Uhura performing a fan dance, or Chekov rehashing his “wessel” shtick fit that conceit?

The short answer is that it doesn’t. Such humor had to be grafted on here, and it shows. It’s forced, awkward, and entirely unnecessary. The inclusion of so much humor actually runs counter to the grandeur and seriousness of the story Shatner hoped to tell.

And then — in a typical bout of bean-counter nonsense — what does Paramount do next? Well, it advertises and markets Star Trek V: The Final Frontier with the ad-line “why are they putting seat belts in theaters this summer?” suggesting that the movie is an action-packed roller-coaster ride! This is after they demanded the movie be a comedy! Talk about assuring audience dissatisfaction. Tell audiences that the movie they are about to see is super-exciting and action-packed, and then give them Vulcan nerve-pinches on horses, Uhura and Scotty flirting with each other, and crewmen singing “Row, Row, Row Your Boat.” Quite simply, The Final Frontier’s marketing campaign didn’t do a good job of managing audience expectations.

The second aspect of Star Trek V: The Final Frontier that damages it so egregiously involves the special visual effects. A movie like this — about the search for God, no less — must feature absolutely inspiring and immaculate, awesome visuals. We must believe in the universe that includes Sha Ka Ree, and the God Creature.

Originally, Shatner envisioned Sha Ka Ree turning into a kind of Bosch-ean Hell, featuring demons and rivers of fire. But what we get instead is a glowing Santa Claus-head in a beam of light, and…a much too familiar desert planet.

What’s worse is that many visuals don’t match-up. When Kirk’s shuttle flies over the God planet initially, the surface of the world looks like a microscopic landscape (a sort of God’s Eye view of the head-of-a-pin, as it were). But when the shuttle lands the planet just looks like a terrestrial desert. This is Heaven?

Perhaps Star Trek V could have surmounted this problem, since the TV series was never about special effects anyway, but about ideas. But the special effects in Star Trek V: The Final Frontier fail to even adequately render believable and “real” such commonplace Star Trek things as starships in motion or photon torpedo blasts. Watching Star Trek V: The Final Frontier is a little bit like watching Golan and Globus’s Superman IV: The Quest for Peace (1986): the cheapness of the effects make you wince, and stands in stark contrast to a franchise’s glory days.

And the editing! Oh my, to quote Mr. Sulu.

Star Trek V: The Final Frontier is edited — in polite terms — in disastrous fashion. During Kirk, Spock and McCoy’s escape on rocket boots through an Enterprise turbo shaft, the same deck numbers repeat, in plain view.

When Kirk falls from his perch high on El Capitan the movie cuts to a lengthy shot of Shatner — in front of a phony rear-projection background — flapping his arms.

And just take a look at how Kirk’s weight, make-up, hair-cut, and disposition shift back-and-forth in his final scene with General Koord and General Klaa aboard the Klingon Bird of Prey. This mismatch was due to post-production re-shoots when the original ending was deemed unacceptable.

Forget the script (which might have worked without the studio-demanded humor). Forget the acting (which is pure Star Trek ham bone — and, in my estimation, perfect for a futuristic passion play), it’s the editing that scuttles this film.Whether it’s allowing us the time to notice that Sybok’s haircut and outfit change on Sha Ka Ree, or permitting us to linger too long on visible wires in two fight scenes, Star Trek V’s cutting is just not up to par.

There’s a Star Trek fan out there on the Net who has taken it upon himself to re-edit Star Trek V: The Final Frontier, and you know something? It’s a worthy enterprise. Preferably, Shatner should do a director’s cut, and trim his misbegotten film down to a mean, lean eighty-five minutes. The worst editing, effects, and jokey moments would be excised, and audiences would be surprised, perhaps, how visually adroit, how dynamic, how meaningful and even spiritual this Final Frontier could be sans the theatrical release’s considerable problems.

Let’s face it, modern criticism often thrives on hyperbole, so it’s fun and dramatic to declare that Star Trek V: The Final Frontier is one of the ten worst science fiction films EVER! The only problem is, it’s not necessarily true.

I don’t even know that The Final Frontier is actually the worst Star Trek film, to be blunt, especially after watching Generations and Nemesis recently. Star Trek V: The Final Frontier conforms to Muir’s Snowball Rule of Movie Viewing. Allow me to explain. Because Star Trek V: The Final Frontier is perceived by the majority of critics and Star Trek fans as “bad,” everything about the film gets criticized, when — in point of fact — many other Star Trek movies feature many of the same goofy errors. For instance, I have read some Star Trek fans complain vociferously about the fact that the Enterprise travels to the center of the galaxy here in a matter of hours.

The fact that in First Contact, the Enterprise gets from the Romulan Neutral Zone to Earth in time to join a battle against the Borg, already in progress, goes unnoticed or at least uncommented upon. So, the starship got there in like, you know, a few minutes, I guess. But because First Contact is beloved and generally evaluated as good, it generally doesn’t garner the same level of negative attention or scrutiny. When it fails in a spot here or there, it gets a pass.

Whereas, by contrast, the details in Star Trek V: The Final Frontier definitely draw heavier scrutiny. The “bad movie” snowball, once rolling down a hill, just grows larger and larger. We forgive less and less. Every aspect of the film is nitpicked and called into question, deservedly or not. It becomes harder, then, to register and recognize the good.

Star Trek V: The Final Frontier is an ambitious failure. But ambitious may be the operative word here. The movie certainly aimed high, and hoped to chart some fascinating spiritual and philosophical ground that feels abundantly true to the Star Trek line and heritage.

But plainly, the execution leaves a lot to be desired. Again, I renew my call for a Shatner-guided 85 minute version. One closer to his original vision, with improved special effects, and better editing. A new official release, re-modulated as I suggest, may be the only way for opinion-hardened Star Trek fans to see the good points of this admittedly problematic entry in the film canon.