The second season of Buck Rogers in the 25th Century is not generally high-regarded among fans. In its sophomore sortie, the Glen Larson series eliminated the characters of Dr. Huer, Dr. Theopolis and the Draconians, downplayed Buck’s (Gil Gerard) strong sense of fish-out-of-water humor, and moved Buck from sexy secret agent work on Earth to a deep space assignment aboard the Earth ship Searcher. These format changes cast the new Buck Rogers rather firmly in the mold of Star Trek or Space: 1999 with the new series acting as a vehicle for “civilization of the week” stories.

In that particular format, success or failure rests largely on how well interesting and likable main characters interact with intriguing or convincing alien cultures.

The Fantastic Journey (1977), for example, got the former aspect of that alchemy right (the likable main characters), but had a difficult time coming up with good stories, and original alien cultures to explore. In broad terms, this was the very problem with the second season of

Buck Rogers. Episodes that involved mischievous dwarves, (“Shgoratchx!), or backwards-aging men spray-painted gold (“The Golden Man”) failed to impress or persuade either mainstream audiences or die-hard sci-fi fans. Some second season episodes were better, including the dynamic “The Satyr”

(reviewed here), a show that pinpointed a great “alien” metaphor for alcoholism and its impact on families.

The subject of this cult-tv flashback, “The Guardians” may not work as effectively as “The Satyr” on a metaphorical level, but I still estimate it’s one of the best episodes of Buck Rogers’ second season, in part because it deploys a tried-and-true Star Trek technique for better developing the dramatis personae.

On Star Trek, an alien disease or weapon was often utilized to examine emotional aspects of the characters that they normally keep hidden. “The Naked Time” or “The Naked Now” are two such notable examples. In those episodes, a disease that mimicked alcohol intoxication “exposed” the underneath characteristics of our favorite Starfleet officers. The character revelations were sometimes funny, sometimes extremely moving.

That general idea informs “The Guardians,” only an alien artifact is the catalyst for the character reveals.

Here, Buck and his new friend Hawk (Thom Christopher) investigate a “Terra Class satellite.” Although the exploration of the planet is supposedly “strictly routine,” Buck and Hawk soon hear a distant bell ringing over the wind’s howl. They follow the noise and discover that the bell tolls for Janovus XXVI, an old man now on his death bed. This ancient “Guardian” informs Buck that he has been waiting for Captain Rogers for over five hundred years. Now, he must pass on to Buck – “The Chosen One,” an ancient green Pandora’s Box. This jade artifact must be transported to the old man’s unnamed successor and only a person of both “the past and the present” (like Buck) can get it to its destination successfully.

That night, Buck sleeps in proximity to the jade box and dreams of his life on Earth. In particular, he experiences a vision of his mother, one from the eve of his disastrous mission on Ranger 3. After the box is brought back to the Searcher, it begins to have strangely deleterious effects on the ship and crew. The ship inexplicably goes off course and makes a setting for the edge of the galaxy.

This trajectory especially concerns Lt. Devlin (Paul Carr), since he is due to be married on Lambda Colony in only a few days.

When Admiral Asimov (Jay Garner) is exposed to the box, he imagines his crew…starving to death on the long journey in the void from the edge of the galaxy to Lambda. When Wilma (Erin Gray) is affected by the box, she sees herself as a hopeless blind woman wandering the corridors of Searcher alone. Then, in a matter of an hour, Wilma is blinded in real life, and realizes her vision was prophetic. Even Hawk is affected, and he experiences an emotional moment with his dead mate, Koori (Barbara Luna).

As the Searcher reaches the edge of the galaxy, Buck realizes the box must be passed on to a Guardian, a “saintly figure” seen throughout many cultures and on many worlds. When a Guardian does not possess the box, chaos ensues, and that sense of chaos explains a lot of Earth’s violent history. Buck realizes that the Time Guardian is the very one that they now must seek…

By and large, Buck Rogers is a pretty light show, a fact which distinguishes it from the original Battlestar Galactica or Space: 1999. There’s often a great deal of humor on Buck, and a tremendous amount of physical action too. In some sense, “The Guardian” showcases how the series could have approached more serious sci-fi storytelling.

This episode is not without flaws (and the ending looks cheap…), but the crew member visions of people starving to death and going blind are authentically disturbing. I remember watching the program for the first time in 1981 and feeling pretty jolted by Asimov’s vision of a crew dying from hunger…and looking like zombies. This moment resonates, and is probably the strongest in the show, despite the fact that Gil Gerard, in the vision, hardly looks emaciated…

“The Guardian” also delves into some pretty dark territory regarding erstwhile Lt. Devlin. While Searcher is lost and heading to the edge of the galaxy, he learns that his fiancé on Lambda Colony has died. She was killed while out searching for him and his lost ship. Again, this bit of drama is just a bit darker than the typical Buck Rogers show, and here it all works well. A sense of panic and anxiety builds up as “The Guardian” reaches it final act.

Frankly, the writing for the main characters here is also amongst the best in the series’ second season. We learn how heavily Asimov carries the burden of command (imagining a future of starvation, in which he is incapable of helping his crew…), we come to understand Wilma’s fear of appearing vulnerable or being pitied. And we are reminded once more of Hawk’s utter isolation and alone-ness.

Of all the phantasms featured in “The Guardians,” Buck’s may be the least effective. It’s great to meet a Rogers family member, since we know very little of the astronaut’s family history, and yet Buck doesn’t really do or say anything important in this dream. You’d think Buck might want to warn his Mom about the coming nuclear holocaust…tell her to go into hiding, or something. Instead, she’s the one worried about his mission.

Buck’s dream is a bit off tonally, though it’s fun to see the special effects from “Awakening” recycled as a callback to the Buck Rogers pilot. In toto, I would have preferred to see a dream in which Buck revealed some personal flaw, foible or fear. Like the fact that he was afraid of never again making a meaningful connection with the world around him. I don’t know. But something other than an idyllic dream of lemonade and small-town Americana. This dream tells us where he came from, but in a sense, we already know that. Better to explore how he feels about where he was, or where he is, or where he might be headed.

Like many cult-tv programs, “The Guardians” also imagines an external force as being the guarantor of peace or war in the galaxy. On the original Twilight Zone, the great (and incredibly atmospheric) episode “The Howling Man” postulated that man would experience peace only during those intervals during which he held the Devil captive. Whenever the Devil escaped captivity, world war would occur.

Likewise, in Star Trek’s “The Day of the Dove,” an alien monster that thrived on “hate” was believed responsible for the violent, war-like aspects of humankind’s long history.

Here, the Guardians preserve galactic peace, but during the uncertain periods of succession, elements of the space-time continuum “jump” their tracks, and chaos is the result. In all these situations, “fate” is determined specifically by some agency outside of man’s dominion and yet he can still struggle to rein the situation back in during each crisis.

Probably the best aspect of “The Guardians” is simply the fact that the episode creates a sense of terror (especially in the scene wherein the box is jettisoned from the ship…but then re-appears aboard her…) without ever focusing on a humanoid villain. There are no bad guys to be found here, at all, only a strange alien artifact that the crew of Searcher, including Buck, doesn’t quite understand.

This conceit was very much of the Space:1999 playbook: terror is forged because man doesn’t have all the answers, and his curiosity or other emotions only create more danger. It’s nice to see Buck Rogers operate on that more intellectual, spine-tingling level, at least for a short duration. Had later episodes followed this relatively intelligent formula, the second season might today be much better perceived.

I don’t often return to the second season of Buck Rogers today because of some of the really dreadful episodes, but “Time of the Hawk,” “The Satyr” and yes, “The Guardians” reveal how the changes from season one to season two could have truly created an interesting space opera and interesting, early 1980s alternative to Star Trek. I don’t know if the second series was too rushed, it was difficult to find good writers, or there were problems elsewhere that needed to be addressed first, but at least for “The Guardians” everything seems to come together for Buck.

In this case “opening up Pandora’s Box” gave the sci-fi series a pretty visceral and intriguing hour.

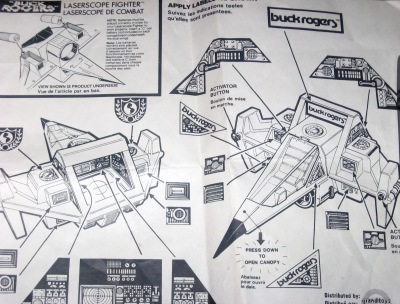

But once I actually got the star fighter for the Christmas of 1980, I could enjoy the Laserscope fighter as a kind of “alternate” ship for the intrepid Buck. The fighter sort of fit with the universe of the TV series, because Buck often ended up going undercover for the Earth Directorate, flying ships of various designs. So it was kind of cool to be able to play out that scenario with a ship other than an “official” one.

But once I actually got the star fighter for the Christmas of 1980, I could enjoy the Laserscope fighter as a kind of “alternate” ship for the intrepid Buck. The fighter sort of fit with the universe of the TV series, because Buck often ended up going undercover for the Earth Directorate, flying ships of various designs. So it was kind of cool to be able to play out that scenario with a ship other than an “official” one.